Is a Taco a Sandwich?

LHSS English Department: Emily Bender, Rev. Joe Cox, Alexia Lopez, Michael Nations, Laurie Schaefer

With the proliferation of social media and the constantly expanding web of news and information, there is no shortage of ideas and opinions in our contemporary society. What’s less common is thoughtful, well-structured, evidence-based ideas. Our English department has been working to graduate students that fill that void—students who can justify opinions, defend arguments, and provide clear reasons for why they think what they think.

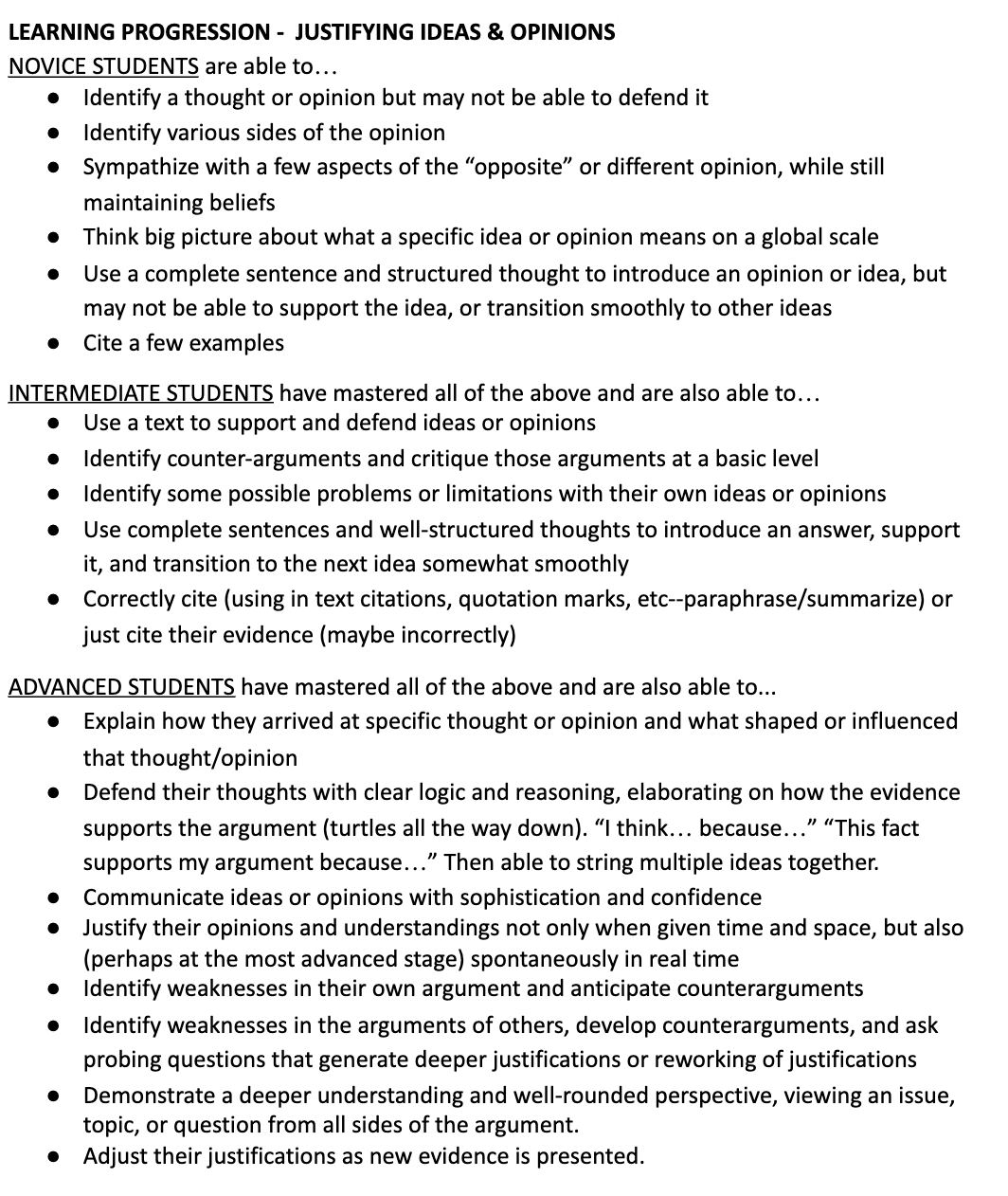

In pursuit of this goal, we recently mapped out three stages of a learning progression, describing the skills and characteristics of students as they move from novice to intermediate to advanced levels of “justifying ideas.”

At the novice level, students can identify thoughts, begin to structure an argument, and sympathize with other opinions. At the intermediate level, students use text to defend ideas, form more structured and complete arguments, and begin to critique counter-arguments. At the advanced level, students defend their ideas with clear reasoning, explain how they arrived at their opinions, recognize and evaluate all sides of an argument, and even adjust their justifications as new evidence is presented.

Arguments and Action Plans

After mapping out this progression, we worked together on a research lesson focused on peer editing for an English II argument essay. Our goal was to teach students to evaluate the strength of each other’s arguments and make useful suggestions for “justifying opinions and ideas.” We structured the lesson so that students would have several opportunities to perform the role of “argument detective” using a response sheet we designed to guide their analysis and feedback. The activity also required the author to review the feedback and commit to an action plan for subsequent revision work.

Our lesson storyline included the following main segments:

Day 1

“Boxing ring” style debate with student volunteers: Is a taco a sandwich?

Introducing the argument analysis sheet (using a clear opinion from the silly sandwich debate). - Article from MN Law Review

Modeling argument analysis - whole class: Smartphone essay example without a clear opinion/position. - Article from Time

Practicing argument analysis - pair work: Electric cars essay example with clear opinion/position. - Article from New York Times

Day 2

Review of work completed on Day 1

Peer-editing with argument analysis sheet

Writer’s reflection and action plan

Lesson Results

After the lesson, we debriefed some of our classroom observations and studied copies of the analysis response sheets from five student pairs. Here’s a brief summary of the student results:

Nearly all of the students correctly assessed whether the peer’s essay had a clear opinion. They were also able to identify the author’s reasons for that opinion. Very few students offered suggestions for strengthening or improving weakly stated opinions.

Over half of the students struggled to differentiate between the opposing position and the author’s attempt to make counterarguments against that position.

Most students (about 80%) demonstrated evidence of meaningful reflection as they reviewed and commented on feedback from peers.

Over half of the students (60%) developed an action plan with at least some specific revisions for improving their arguments. This is better than what we typically see with peer editing, but still leaves much room for improvement.

A Promising Example

Perhaps most striking, however, was the insights we discovered while reviewing the editor-author exchanges between specific student pairs. One helpful example was from Henry and Tiana. Henry was one of the few students that provided specific revision suggestions for each section of Tiana’s essay. He not only summarized her main arguments but also provided examples and ideas to enhance the argument, the opposition and the author’s rebuttal. In a corresponding fashion, Tiana’s reflection and action plan was among the most thoughtful and specific in the class. She clearly reviewed the comments from Henry and wrote specific plans for incorporating these revisions.

Drawing on these examples, we noted an important pattern that emerged in the student results—when students had specific guidance and revision suggestions from the editor, they were more likely to be reflective with clear plans for revision. However, neither our modeling exercises or the analysis sheet focused on providing revision suggestions. Instead, we had primarily instructed students to study the essay, assess the clarity of the argument, and synthesize the reasons for both positions. If we wanted more editor-author exchanges to resemble Henry and Tiana, then our analysis sheet needed to facilitate these kind of suggestions. We also needed to be more intentional about teaching and using consistent terminology (claim, counterclaim, rebuttal) so students could build a common language and clearly distinguish each component.

Argument Analysis 2.0

In this lesson, we discovered that providing students with a specific framework for analyzing a peer’s essay gives structure and direction to the feedback process. It helps students’ improve each other’s writing, but also helps them develop skills and patterns of reflective analysis for their own writing and self-editing.

We also learned that incorporating a “reflection and action plan” with peer editing is a useful tool for helping students process feedback and evaluate each essay element in smaller chunks. Given this kind of deliberate and clear opportunity for reflection and revision planning, students demonstrate a more thoughtful and serious response.

In addition, when students receive specific guidance and suggestions from a peer editor, they are more likely to be reflective with clear plans for revision. By learning to perform both of these roles, we hope students will not only enhance each other’s arguments, but also become more practiced and effective at finding holes in their own arguments, both in academic settings as well as personal and professional relationships.

With these insights in mind, the team designed a new Argument Analysis Template with substantial adjustments to both the analysis prompts and the “reflection and action plan.” Listed below are links to the “before” and “after” versions of the template, the latter representing what we hope will be an foundational tool for the department. Our goal is to use this tool, and the framework it represents, to standardize the way we teach argument, analysis, and debate across the curriculum, and to foster a schoolwide culture of evidence-based claims.