The Sound of a Good Argument: Claim, Evidence, Reasoning

FLHS Physical Science Team: Emily Blank, Mark Cheney, Christian Egger, Corie Naugle, Taylor Tonniges.

In the science classroom, few things are more important than learning to formulate a sound argument. Yet, despite years of experience writing lab reports, most high school students still struggle to construct and communicate evidence-based explanations.

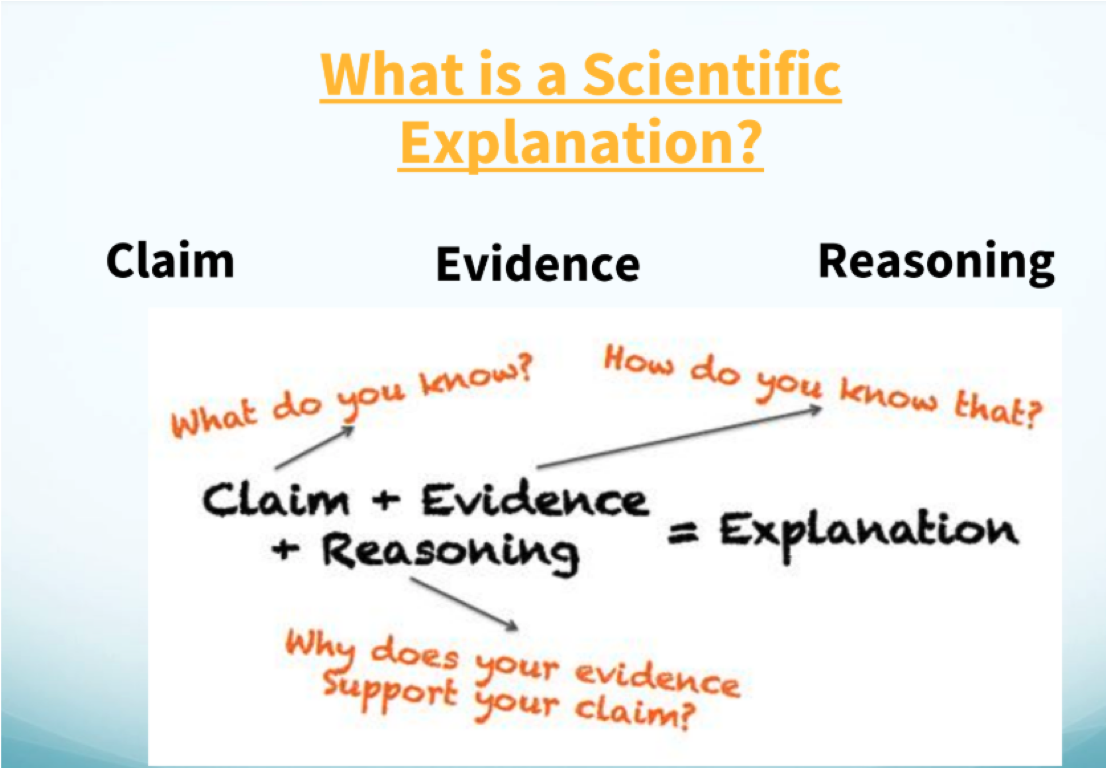

The physical science team has been working to address this challenge through the Claim, Evidence, Reasoning (CER) framework (developed by Katherine L. McNeill of Boston College and Joseph Krajcik from Michigan State University).

The Claim is a conclusion statement that answers a specific question. What can you conclude? Was the hypothesis proven correct or incorrect?

The Evidence is your data that support the claim (tables, charts, graphs, observations). What facts led you to make the claim?

The Reasoning is a detailed explanation for why the evidence led you to make the claim.

It also includes an explanation of the scientific concepts that are relevant to the claim. Why is this evidence important? Why do the facts support the statement?

In a previous project focused on problem solving, the team found that a solid introductory lesson at the beginning of the year effectively set the stage for the knowledge and skills they hoped to reinforce throughout the year. They adopted the same approach with CER and introduced the framework for 10th grade students in combination with an online learning lab early in first semester.

Learning to Use CER

The lesson started with a lively discussion about social norms. Students analyzed an example claim that “student fact surveys are not true, because everyone lies” and they identified both the claim and the reasoning elements of that statement. It was a helpful way to introduce the discussion of why claim, evidence, and reasoning are important skills to develop.

Next, the teacher explained the parts of the CER acronym, including a list of words to serve as “linking prose” that connect evidence back to the claim. The teacher also explained the criteria that would be used for evaluating written responses.

Answer is in paragraph form

Correct argument

Evidence that supports their argument (referring to scientific principles, diagrams, graphs, equations, and perhaps calculations)

Presented in logical order

Linking prose between concepts

Makes sense on first reading

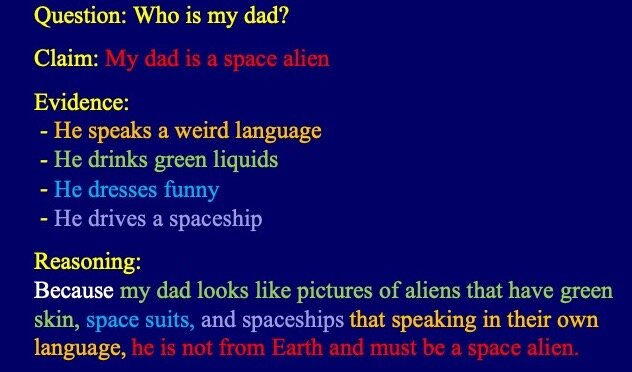

Students then studied some additional examples to apply the CER framework as a class, beginning with an Audi car commercial where a little girl claims her father is a space alien.

After watching the video, they used used color-coding process to analyze the reasoning behind the girl’s claim.

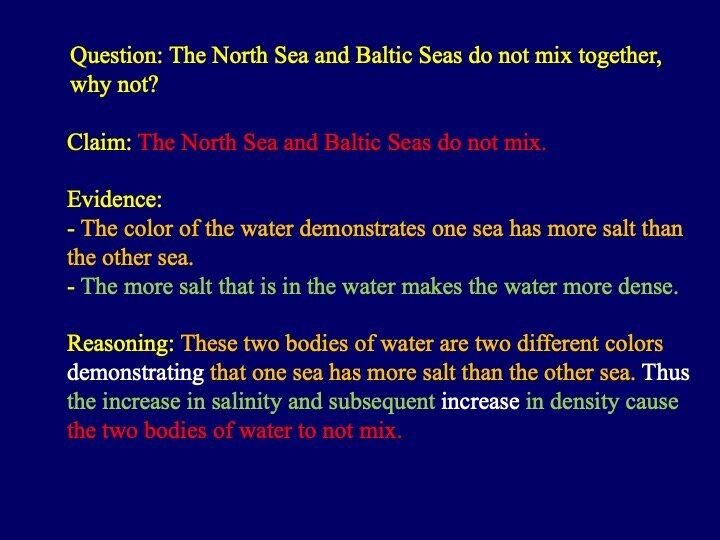

The students also worked together as a whole class to compose a CER color-coded response for a scientific question about density: The North Sea and Baltic Seas do not mix together, why not?

Online Discussion Forum and Density Lab

The second half of the lesson took place as part of a discussion forum and CER writing task during the online Density Lab. The teachers carefully crafted a series of instructions that would help students reflect and apply the CER framework within the constraints of the online context.

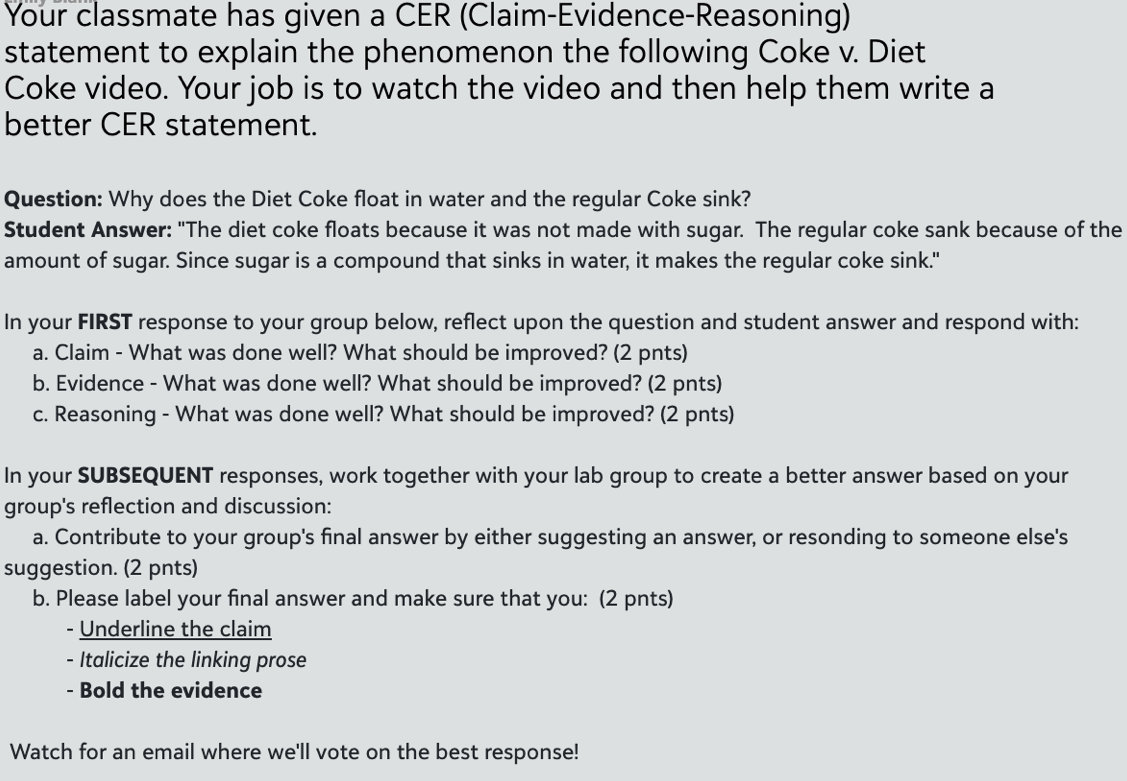

Students were asked to watch the following Coke vs. Diet Coke video while considering the question “Why does the Diet Coke float and regular Coke sink?”

Students then analyzed an example student response and used the online discussion forum with their lab group to compose a better explanation.

Finally, students worked through the assigned tasks for the Density Lab, including responses and explanations that required CER. The science team examined these responses as well as the discussion forum responses during their post-lesson debrief meeting.

Student Results

Student results were particularly strong in stating the correct argument, presenting a logical order, and using prose to link concepts. Most students were also able to put their answer in paragraph form. Most of the paragraphs, however, did not make sense on the first read, and students struggled with using evidence to support arguments.

CER Reflections

The teachers anticipated that teaching the CER acronym and color-coding other examples would be the most critical parts of the lesson. The rationale was that students use of sound explanations would improve after helping them adopt habits of self-regulation--intentionally reflecting on the use of CER, identifying gaps in their own arguments, and working to improve their use of each component. The CER acronym would help students formulate an answer, while the coding would help students reflect on their response to judge whether it was sufficient. They also anticipated the online discussion forum would help students practice applying CER and look for gaps in reasoning, prior to completing their responses for the Density lab.

Based on the results, the team concluded these instructional elements were indeed helpful in improving students’ recognition of CER components. Applying the acronym with the Baltic Sea example also helped students sequence their arguments in a logical order. The online discussion thread replicated a classroom lesson with graduated stages of reflection and the in-class activity followed by the discussion thread helped scaffold reflection practice. In addition, the online format provided the unexpected advantage of documenting each student’s thinking and level of analysis.

Example Student Exchange from Online Discussion Thread

Student results also revealed that using evidence and making clear arguments remained areas of continuing need, particularly for students in the fundamentals course. As recorded below, teachers identified several important challenges to address in their ongoing planning and collective work.

Students’ answers included something they thought was evidence, but it was not complete and sometimes not correct. We need to continue thinking about whether students not listing all of the evidence is a function of them not understanding the concept of density or a function of them not being able to articulate it.

The small answer space on the Google Form does not lend itself to seeing the entire answer and makes it less likely that students reread and reflect on their answer using CER. We need to address this with students and make sure it’s not a limiting factor in the quality of their responses.

Students included a surprising number of incorrect/irrelevant statements in their responses, and these results also often correlated with the paragraphs not making sense on the first reading. We need to come up with ways for teaching students how to think through and recognize incorrect/irrelevant statements (e.g., place an irrelevant statement in the discussion thread group example).

We need to teach students how to translate the individual components of CER into a coherent paragraph answer.

We had originally defined Criterion 5 as an answer containing linking prose as evidence of reasoning. As we examined answers, we realized that not all linking prose ensures an answer is well-reasoned, but well-reasoned answers include linking prose or evidence presented in a logical order. We changed our criteria to not just include linking prose, but to require the prose to wrap the evidence back around to the claim. We also need to reconsider our definition of reasoning and make other changes to our criteria. Proposed new criteria:

Write your answer in paragraph form.

Make the correct argument.

Support your argument with relevant scientific evidence. (examples)

Connect evidence with linking prose.

Read your answer. Is it logical? Does it make sense on the first reading?

When teaching scientific concepts, it will be helpful if we, as teachers, reinforce that each concept is a piece of evidence that connects from one to the next in order to support an argument. For example: Valence electrons connect electron configurations to the octet rule. The octet rule connects valence electrons to why atoms bond in different ways.

Closing Thoughts

A recurring theme in the teachers’ post-lesson discussion was the importance of distinguishing between students’ scientific understanding and students’ ability to apply CER. CER enables students to articulate newly formed knowledge and ideas, but when conceptual understanding is weak, reasoning breaks down. Both are necessary for teaching and learning. Both should be taught and assessed. And both are essential for making sound arguments.